YOUR PHYSIO

Condition directory

Knee Osteoarthritis

What is Knee osteoarthritis?

4.1million people in England have osteoarthritis (OA) of the Knee. 18% of the population aged over 45 years old has the condition.

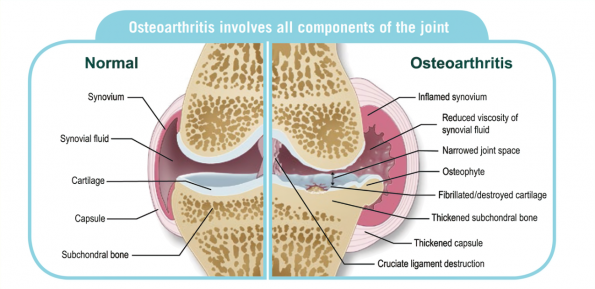

Osteoarthritis is a condition which affects the cartilage of our joints, causing it to become thinner.

Cartilage is a layer of smooth material which lines the ends of our bones in our joints. It acts as a shock absorbing layer, like an in-built suspension system in our joints, to try to protect the ends of our bones from too much stress and strain.

Other structures within our joints may also be affected in osteoarthritis, including the lining of the joint capsule (which helps to provide fluid, lubrication and nutrition to the joint) and the underlying bone, which can both become inflamed leading to pain and swelling.

Why does osteoarthritis hurt sometimes, but not always?

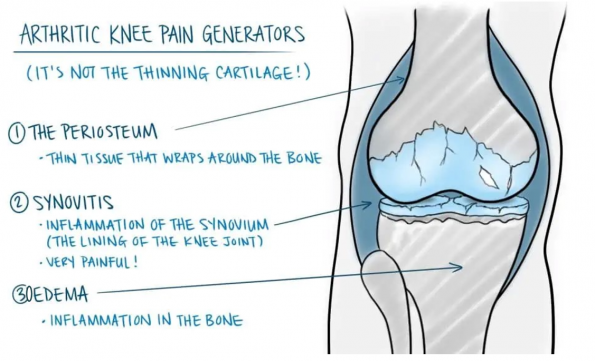

Thinning of the cartilage due to osteoarthritis can mean that we have lost some of the shock absorbency from within our joints. This means that it is easier to “overload” the bones just underneath the cartilage surface, which can cause them to become irritated and inflamed, causing pain. Additionally, the lining of the knee joint (the synovium) may become inflamed.

It is this inflammation (irritation and swelling within the bones and joint) which is the cause of pain in arthritic joints, not the thinning cartilage itself. Therefore, it is quite common for people to have arthritic changes in their joints, but without any pain. If the cartilage is thinning, but the underlying bone and lining of the joint aren’t inflamed, then there may be no pain at all!

What causes Osteoarthritis?

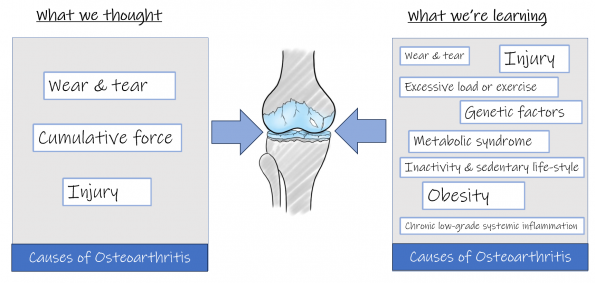

We used to believe that cartilage thinning in osteoarthritis was caused by “wear and tear”, and therefore the more you used your joints, the more “worn” they would become, until eventually you developed arthritis and potentially wore your cartilage out completely. We appeared to believe that it was a forgone conclusion that the arthritis would progress to the point where you would need a joint replacement, and that attempts to manage symptoms with self-management approaches was just “covering up” the problem or “putting off the inevitable”.

We now know that arthritis is a much more complicated process than simple wear and tear. Our cartilage is a living tissue, and like other tissues within our body it is able to adapt, repair, grow and respond to its environment throughout our lifetime. It is constantly going through a cycle of wear, repair, and adaptive change, similar to the changes we can see in our skin: old skin cells are constantly replaced by new skin cells; and skin can adapt to be thicker where that is needed (on the soles of our feet for example).

We now understand that there are many factors that can disrupt the delicate balance between these “wear” and “repair” mechanisms, so that the process of “wear” becomes greater than the rate of “repair” for our joint cartilage in certain circumstances, which can ultimately lead to cartilage thinning and osteoarthritis. Some of the factors that can contribute to this include:

Injury to the joint, or previous surgery

Particularly fractures which have affected the joint, any injury which caused a bleed into the joint, or any previous cartilage or meniscal injury +/- subsequent surgery.

Genetic pre-disposition

You are more likely to develop osteoarthritis if your parents also suffered from this.

Excessive load/exercise:

For example, ultra-distance athletes, professional athletes, or those in the military or fire service; possibly due to repeated minor injuries without adequate opportunity to heal, or due to general “overload” of the joint structures. There is no evidence that "normal" loads and activity levels, such as regular running or manual jobs, lead to any increased risk of arthritis; in fact the opposite is likely to be true, with many studies demonstrating a lower risk of arthritis amongst those who run regularly or do regular physical activity.

Obesity:

We used to believe that obesity increased the risk of arthritis due to increased strain on joints, but this has never explained why obesity also increases the risk of arthritis in our joints that aren’t considered “weight-bearing” such as our thumbs. We now understand that obesity is linked to many chronic diseases because of the effect that fatty tissue in our body has on the development and maintenance of inflammation, as well as the maintenance of healthy cartilage metabolism in arthritis (the wear, repair, and adaptation process described above). What this means is that the more fatty tissue we have in our bodies, the more fatty chemicals and hormones there are which seem to have a negative impact on our body’s ability to control inflammation and maintain healthy cartilage, both of which contribute to the development and progression of arthritis.

Inactivity/sedentary lifestyle:

We know that regular, recreational exercise has a protective effect when it comes to arthritis. Regular weight bearing and resistance (strengthening) exercises have been shown to:

- Increase muscle strength

- Increase bone density

- Increase cartilage health and thickness

- Reduce the amount of inflammatory chemicals in our joints and our circulating blood

- Reduce the amount of chemicals in our joints that inhibit the cartilage repair process

Whilst inactivity, or avoidance of exercise, has been shown to:

- Reduce muscle strength

- Reduce bone density

- Reduce cartilage health and thickness

- Increase the amount of inflammatory chemicals in our joints and our circulating blood

- Increase the amount of chemicals in our joints that inhibit the cartilage repair process

We’ll talk more about the benefits of exercise in arthritis later.

Metabolic syndrome:

Metabolic syndrome is the name for a group of health problems that put you at risk of type 2 diabetes or conditions that affect your heart or blood vessels (It does not include rare genetic metabolic conditions), and have also been linked to the development and progression of osteoarthritis. These conditions include:

- Obesity (particularly with fat accumulation around the stomach)

- High blood pressure

- High blood sugar levels due to insulin resistance (leading to type 2 diabetes): this can trigger low-grade systemic inflammation in the body, which can contribute to the development or progression of arthritis.

- Dyslipidemia (an imbalance of good versus bad cholesterol and other lipids in the blood): can increase your risk of heart disease and stroke and is also associated with increased risk of arthritis development and progression, as the “bad” lipids can lead to inflammation and can also directly interfere with the reparative process of our cartilage.

Whilst this all sounds very complex, it means that we now understand that arthritis isn’t an inevitable part of aging, is not caused by being active, and doesn’t necessarily have to result in a joint replacement. It has also improved our understanding of why certain “core” treatments work so well in the management of osteoarthritis, such as exercise and weight loss.

What are the treatment options for Knee osteoarthritis?

The core treatments for osteoarthritis are:

1. Exercise

2. Weight loss

Click on these headings for further information.

Treatment options for Knee Osteoarthritis

Treatment options: Exercise & Activity

Treatment options: Weight Loss